Miami’s favorite son, Dwyane Wade, enters Hall of Fame

Dwyane Wade enters the Hall of Fame as one of the top two-way guards in NBA history.

On the evening of Nov. 7 in 2005, Pat Riley, president of the Miami Heat, made a decision that was well-meaning at that time. He raised a No. 13 jersey to the rafters of the arena, not in honor of any Heat player, but for Dan Marino, the former All-Pro quarterback of the Miami Dolphins.

Riley’s intentions were respectful if unconventional. Marino, Riley explained, was the greatest athlete the history of South Florida. So that’s where the Dolphins jersey belonged — even in a basketball arena.

Yet on that same night, in that same building, a third-year Heat player began chipping away in earnest at that declaration. Dwyane Wade scored 23 points with six assists in a victory against the New Jersey Nets, a tasty tease of far bigger games and moments to come, much sooner than later.

By summer, Wade was ready to embark on the road to Springfield, Mass., home of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. But first, it detoured through Dallas, where Wade executed a thorough dismantling of the Mavericks with an NBA Finals performance for the ages. He averaged 34.7 points, coming through multiple times in the clutch during the series, and at 24 was the fifth youngest to be awarded Finals MVP.

That was just the appetizer. What followed was basketball brilliance spread over 16 seasons, 14-plus spent with the Heat. Wade won two more titles in Miami for three total, made 13 All-Star appearances, was named All-NBA eight times, All-Defensive three times, led the gold medal-winning Team USA in scoring at the 2008 Olympics and became the Heat’s all-time leader in points (21,556), assists (5,310), steals (1,492) and games played (948).

Five signature clutch plays that defined Wade’s illustrious career.

All along, that Marino jersey continued to hang above, while shrinking in stature, because the original meaning behind it soon became outdated. Even the man who put it there conceded as much.

“I’m pretty biased about it, but for his tenure here he’s probably the most respected, admired professional that we’ve ever seen in this state,” Riley told NBC 6 South Florida.

He was talking about Dwyane Wade now. Not Marino. Not any longer. The conversation changed.

But why confine Wade’s impact to a region? As he prepares to join the other greats in Springfield this weekend, Wade’s qualifications place him near the very top of those who ever played his position.

He was, essentially, the prototypical big guard at 6-foot-4, with the ability to score multiple ways, make game-winning shots yet remain unselfish with the ball, blessed with the strength needed to rebound in traffic and the anticipatory skills required for defense. Above all, he brought the fiery competitiveness that separates the greats from all others.

“When I look back on it,” Wade said in 2019, “I’ve done everything I could.”

He did enough in basketball to earn the ultimate honor of being known on a nickname basis to the world: D-Wade. He came to Miami at the right time; the franchise began to regress after enjoying a spirited run — but no title — during the Alonzo Mourning/Tim Hardaway years of the mid-to-late 1990s. Riley stepped away from coaching (temporarily, as it turned out) and moved to the front office. The Heat needed a fresh face for a new era.

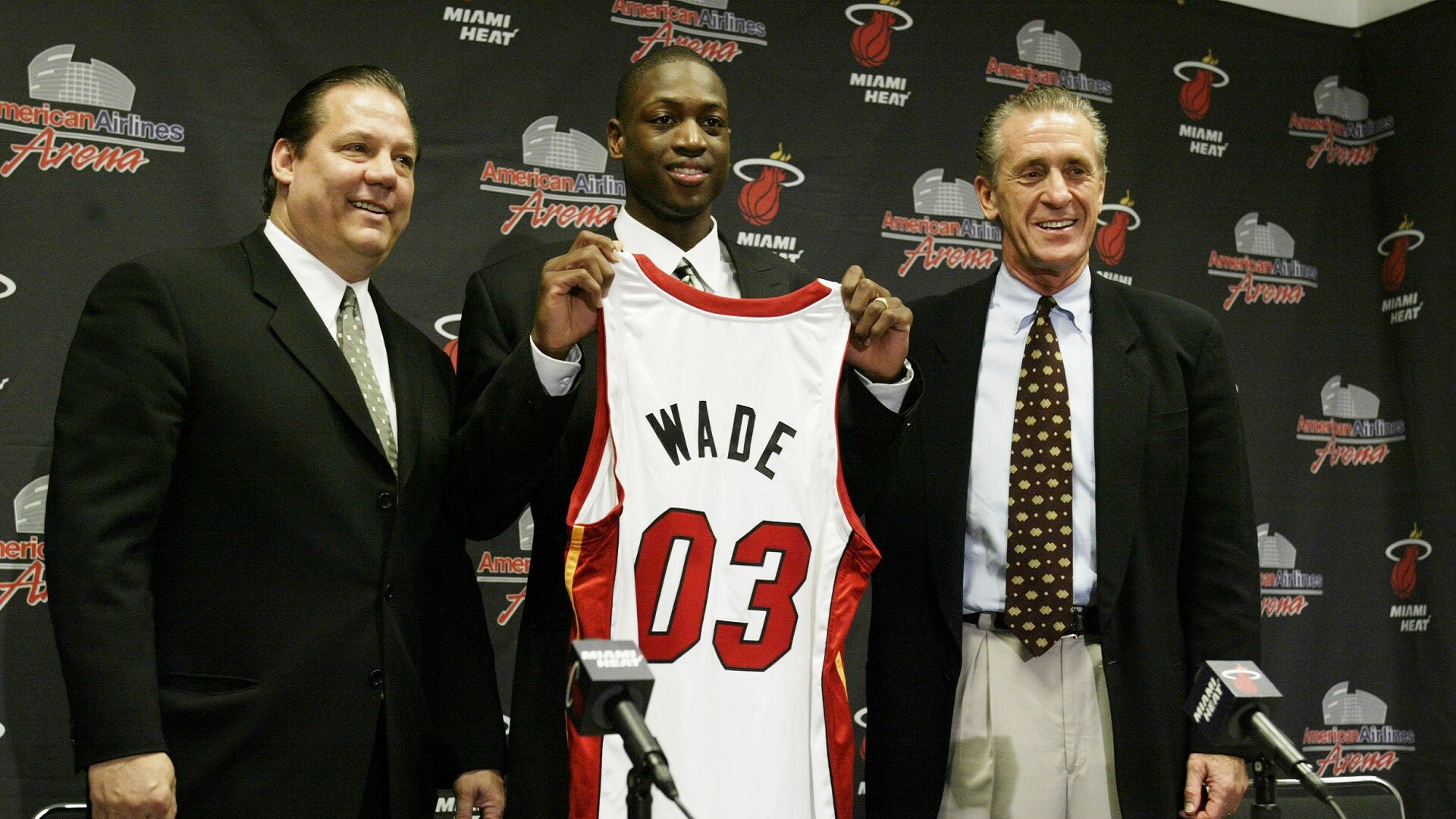

Heat executives Randy Pfund (left) and Pat Riley introduce the freshly-drafted Wade to Miami’s media.

Wade seemed like an unlikely candidate for superstardom at first. He was very good in high school but not the best that a hoops incubator like Chicago had to offer. He wound up at Marquette, a fine basketball school but not a blue blood, mainly because poor academics limited his college options.

He was taken fifth overall in the 2003 Draft, certainly high enough to inspire hope for the Heat, but that Draft was top-weighted by the presence of LeBron James, a generational prospect.

In his rookie season, and his first taste of playoff action, Wade hit an acrobatic floater just before the buzzer to beat New Orleans in the series opener. But that’s not when Miami knew it had someone special.

That offseason, the Heat engaged in trade talks for a blockbuster: Getting Shaquille O’Neal from the Lakers. The trade negotiations initially centered around Wade because that’s who the Lakers wanted in return. And Riley told them no, only in much spicier terms. That’s when everyone knew that Riley saw more value in Wade, even if it cost them Shaq.

So what happens? Shaq arrives, larger than life, and as the season progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that Miami is Wade’s team, even with O’Neal on it. Wade led the Heat in scoring, and the following season, once the 2006 NBA Finals arrived, there was no doubt. The ball belonged to Wade in the moments of truth. He was the lead singer. He delivered the franchise’s first title. And he was just getting started.

“When Shaq came, it really inserted that level of confidence in me that I could be one of the greats,” Wade said. “I mean, I needed somebody that was a great to be able to show me what it’s like to be great. When Shaq says, you’re going to be one of the greats, I don’t need no more juice than that.”

The Miami Heat legend and future Hall of Famer looks back at his 16-year career filled with memorable moments.

Wade became part of a post-Michael Jordan wave of young talent that would define the league in the 2000s. And by his third season, he was already elevated among the very best two guards in the game.

His sixth season in 2008-09 was his peak and, all things considered, one of the best campaigns in decades by anyone. He led the league in scoring at 30.2 ppg along with career highs in assists (7.5), steals (2.2) and blocks (1.3). It was a level of all-around excellence rarely seen in the league, especially from a player under 6-5; the best comparison was a prime Jerry West.

Wade finished third in the MVP voting that season, yet had higher scoring, assists, steals and blocked shot averages than the winner (James) and the runner-up (Kobe Bryant). Wade was also third in Defensive Player of the Year voting.

Wade’s offensive game was flavored by a combination of energy, athleticism and creativity. His trademark was the mid-range jumper and he mastered the “Eurostep” by squeezing past defenders for layups. That made him a tenacious player in transition, running downhill but able to stop on a dime if necessary. He was a fearless dunker who would challenge anyone at the rim, no matter their size. Wade was never a volume 3-point shooter and shot less 29.3% on 3-pointers, but he still averaged 22 ppg in his career.

His defense remained sharp during his prime years; Wade averaged more than 1.5 steals for 11 straight seasons and more than a block per game in six. Including the postseason, Wade blocked more shots than any guard in history (1,060) despite standing two inches shorter than No. 2 Michael Jordan.

Despite standing only 6-foot-4, Wade rejected shots better than some big men.

Therefore, Wade played 94 feet. His impact was all over.

“He’s the player I always respected, always wanted to copy,” Jimmy Butler said during the 2023 Finals. “His presence is everywhere in Miami even though he’s retired. He played the right way, the way I want to play. Now, I just want to win championships like him.”

Wade’s biggest challenge was perhaps when LeBron arrived in Miami in 2010. Wade by then was an A-lister in the league and the franchise centerpiece, and now, someone greater wore the same uniform. This was different from O’Neal, who was starting the twilight of his career when he arrived in Miami and would only play 3 1/2 seasons there. LeBron cast a larger shadow … a more dominant one.

Wade was an unselfish player and one of the game’s better passers at his position, so that wasn’t an issue. However, could Wade’s ego handle it? Years later, he admitted that it was tougher than he thought. His pride often interfered, but not for long — not when their friendship grew and the championships followed.

Watch as the Miami Heat battle through an intense NBA season to win back-to-back championships.

And so, how Wade changed his game to accommodate James and became an even better team player, added another layer of greatness to his already-impressive body of work.

“I’ve played so many roles my entire basketball career,” Wade said in a recent interview with Shannon Sharpe. “And I think that’s why I look at myself as one of the greatest players, because I didn’t do it one way. I showed you how to be great in so many different ways and so many different times; my game changed and evolved so much.”

Dwyane Wade and LeBron James won consecutive championships together with the Heat in 2012 and 2013.

Wade received one of the ultimate honors in 2022 when he was named a member of the league’s 75th Anniversary Team. And now, he’ll have real estate in the Hall.

Then there’s that issue of being a local icon, for what it’s worth. Even with four years of James and that ever-present Marino jersey hanging overhead as a nightly reminder of another all-time great, Riley believes the Miami mantel belongs to one player.

“LeBron was here for four years, but Dwyane was here for a lifetime,” Riley said. “I don’t think you’ll ever see another player like Dwyane in any sport that’s going to surpass him.”

And that includes Lionel Messi, the soccer legend who arrived in July to play for the MLS’ Inter Miami and the latest “threat” to Wade, for those suffering from recency bias.

Because, and this is no offense to James and Marino and any number of greats who’ve come through South Florida, but how many have had an entire municipality “renamed” in their honor?

The city of Miami, the Heat and any team that calls the 305 home will always be residents of “Wade County.”

* * *

Shaun Powell has covered the NBA for more than 25 years. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Warner Bros. Discovery.