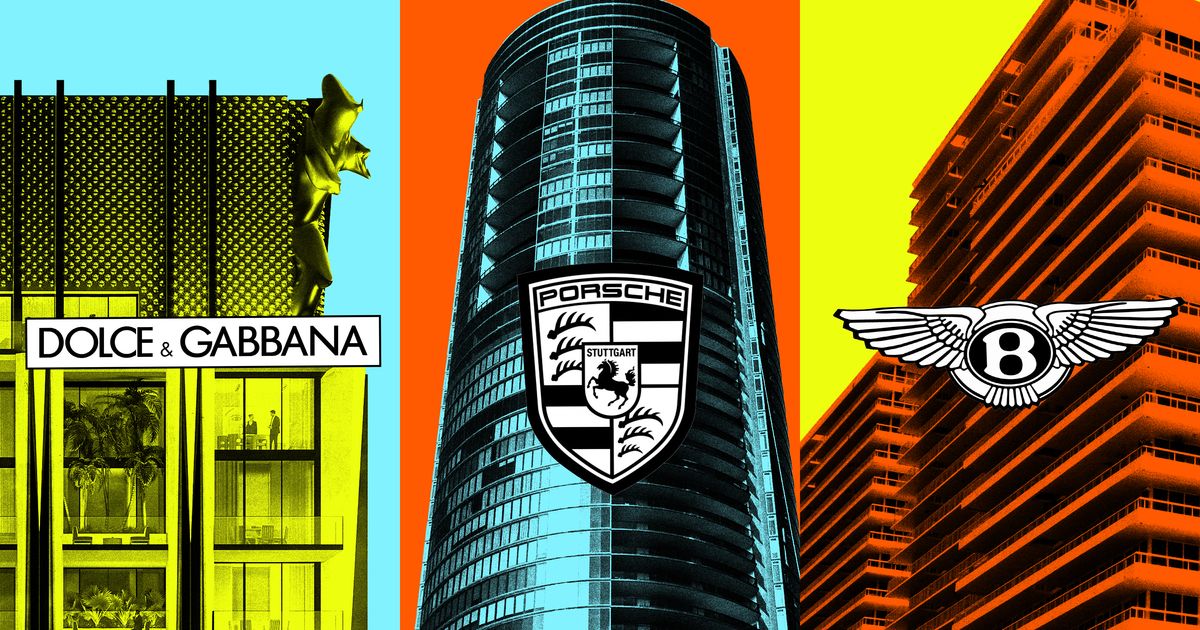

Why So Many of Miami’s New Luxury Towers Are Branded

Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photos: Bentley, Dolce & Gabana, Getty, Porshe

Major Food Group, the restaurateurs behind Carbone and Dirty French, didn’t open a Miami outpost until 2021, but it, like its New York counterpart, became an impossible reservation within the first month (Forbes noted that there were, almost immediately, round-ups of where to eat when you couldn’t get in). The company threw itself into feeding the pent-up demand, adding five other restaurants there and ZZ’s Club, a members-only spot which quickly built up a 5,000-person waitlist. (This time, New York came second: The ZZ’s Club in Hudson Yards didn’t open until last fall.) Soon, its burgeoning hospitality empire will branch out beyond the restaurant world, in the form of a 58-story copper-faceted luxury tower on the Miami waterfront, with 6,000-square-foot full-floor apartments and a rooftop helipad.

This does not strike anyone in Miami luxury real estate as the least bit strange. If anything, it’s surprising that Major Food Group, with its celebrity clientele, buzzy restaurants, and outposts in Doha, Dallas, and Hong Kong, didn’t affix its name to a Miami condo project sooner. Pretty much everyone else has: Porsche, Aston Martin, Mercedes, Bentley, Pagani, Armani, Fendi, Missoni, Dolce & Gabbana, Cipriani. Diesel, the early aughts denim brand known for its edgy marketing and belt-size miniskirts, has one. So does the Well, a Flatiron health club that only opened in 2019. Even Elle, as in the magazine, has announced that it, too, is doing a branded residence.

A rendering of the Dolce & Gabbana tower in Miami, with gold and bronze highlights on the facade and an open-air amenity deck on top.

Photo: Courtesy JDS Development Group and LL&CO

“It’s nothing short of wild how many branded developments there are,” says Peter Bazeli, a real estate development advisor and principal at consultancy Weitzman. It started off with brands like St. Regis and Waldorf Astoria, but these days seemingly any brand will do, and in Miami, it’s becoming a rarity to build anything without one attached. “Now it’s expected,” says Bazeli. “The traditional residential model of just building a really nice building is not enough anymore. Each new development has to have a brand, has to conjure up the idea of what the lifestyle can be.”

While branded residences have recently reached a fever pitch, the trend has been around for decades. The Sherry Netherland on Fifth Avenue, thought to be the first, dates to 1927. Hotels soon followed, but the current incarnation of branded condos — with less, say, intuitive partnerships — took off in Miami ten to 15 years ago, around the time the Porsche tower was announced. (They’ve also been huge in Dubai, which makes Miami look restrained in comparison.) They made perfect sense in a city with so many foreign buyers and an abundance of new developments, says Oren Alexander, who, alongside his brother, Tal, and several others, heads up the brokerage Official. Unlike New York, where the address — Park Avenue, Fifth, Riverside Drive, Central Park West, Bleecker — is the brand, in Miami, buyers needed something more to grab onto. An address on Brickell or Collins Avenue doesn’t tell you much, and most foreign buyers don’t know the difference between, for example, Related and JDS. “What they do know is brands,” says Alexander. Or, another real estate insider put it: “New York is the brand — there’s an authenticity to the city and the neighborhoods. In Miami, the brand is the brand.”

The 66-story Aston Martin tower in Miami has a sail-like profile.

Photo: Courtesy Aston Martin

A glassy luxury tower in Sunny Isles or Brickell becomes more alluring, at least to a certain type of buyer, when it’s the Porsche tower, the Four Seasons Residences, or condos by Dolce & Gabbana. It’s win-win-win: developers sell condos faster — brands have built-in customer bases they can tap, brokers say, with superfans who will buy Aman or Ritz-Carlton residences in multiple cities — and pay significantly more than they otherwise would (hotel-branded residences sell for a 30 percent premium). Brands get licensing fees, a cut of sales, and a ton of free marketing. And buyers, besides the thrill of swimming beneath a giant Mercedes logo, get the assurance that a company they adore and trust has signed off on the design and finishes. Surely, Bentley isn’t going to risk its reputation on a subpar product?

Karen Elmir, an agent at ONE Sotheby’s International Realty, saw this firsthand. “When they launched sales at the Mercedes tower, it was a frenzy,” she says. This spring, JDS, the developer, sold 100 units in just four days off floor plans — the model unit isn’t even open yet. Real-estate professionals are more skeptical: It’s a huge building, originally intended to be a rental, in what was described to me as a second-tier location. And no one really knows what Mercedes is bringing to the project. Besides its name, that is.

The Diesel Living condos in Wynwood, Miami.

Photo: Courtesy Diesel Wynwood

And this, brokers say, is the big question when it comes to the latest wave of branded residences. What, exactly, do people get when they buy there? The hospitality-branded residences were (and remain) popular because buyers know what to expect from an Aman or a Ritz Carlton: the atmosphere, the level of service, the food and dining options. “These brands have trained personnel who know how to treat people, and they don’t only put their name on it, they also operate it after it’s finished,” says Edgardo Defortuna, who heads up Fortune International Group, the developer behind St. Regis Sunny Isles. “It’s a sophisticated, resort-type experience.”

But what about at a fashion- or car-branded tower? “There are brands like Missoni that don’t really add value beyond some peachy upholstery on furniture in the lobby,” says a broker. “Fendi — that’s another one, who gives a shit?” says another. “Do I get a handbag when I buy a one-bedroom? Is Fendi working with a famous Italian designer who is doing the interiors? Is there a furniture package?” (The interiors, for the record, were “curated” by Fendi Casa, according to the New York Post). The branded towers do allow companies to show off their homeware lines, with mixed results — i.e., Bugatti’s debut furniture collection. And when Major Food Group broke off its partnership with JDS on 888 Brickell, Dolce & Gabbana moved in — creating an impression that, contrary to all the marketing, brands might not suffuse every aspect of a building from inception to operation.

The Missoni Baia residences in Miami are the brand’s first residences in the world.

Photo: Courtesy Asymptote Architecture / Hani Rashid + Lise Anne Couture

Say what you will of Miami’s Porsche tower: At least it fully committed to the bit. The building has an elevator that whisks residents’ cars to sky garages off their apartments. There isn’t even a designated pedestrian entrance. Residents drive in beneath a Porsche Design sign and go straight up to their apartments, park, and walk into their homes, where they can gaze upon their cars any time they want through the glass walls of their garages. (Regular units have two car garages and penthouses have four.) Volkswagen executives were reportedly so taken with the tower that they offered the developer, Gil Dezer, any other luxury-car brand he wanted for his next tower. He went with Bentley. “The Porsche tower, I didn’t love it, but it was a really significant concept,” says another developer.

For what it’s worth, Major Food Group, which partnered with Terra and One Thousand Group, is promoting its standing in the food world through its project, callled Villa Miami. Its building will offer residents the chance to be fully immersed in all things MFG: kitchens designed by Mario Carbone, a double-decker restaurant and bar, juices and healthy snacks served up poolside, private-chef services, VIP status at all the other MFG restaurants, and Sadelle’s coffee and bagels every morning. “It’s not about having a label,” said David Martin, the CEO of Terra, which has also partnered with Cipriani on a building. “It’s about trying to create an ethos.” It was, he noted, called Villa, “not the Carbone tower.”

There are some downsides, of course. Fendi, one broker tells me, “ended up doing really well, but I think it would have done the same or even better if Fendi wasn’t on the door.” The condo was in Surfside, an area popular with American buyers, who he says bought units despite, not because of, the branding; they “thought it was cheesy.” In addition to the buyers who don’t want to be identified with brands at all, there are others who identify so strongly with their favorites that they won’t buy from a rival — like the Ferrari guys who can’t bear the thought of living in the Porsche tower.

A few projects have also tarnished brands who make the mistake of associating with something that’s not up to par, like Armani’s Sunny Isles project, according to one real-estate insider. “They branded that after a pretty successful residential project at 20 Pine in Manhattan,” he says. “But it ended up with a transient, tourist occupancy — people traipsing through the lobby with suitcases. It did not fit the classic Armani vision, an Italian fashion crowd.” But, he added, they seem to have recovered with a very well-received project on the Upper East Side. (That project, with just ten units versus 260, and much higher price points, did attract the classic Armani crowd, including Giorgio Armani himself.)

Things start to veer into the ridiculous when brands like Pagani, a tiny supercar company, throw their names behind condos. It’s a logical match in some respects (design, high-end materials, rich clients), but the company will probably make more condos than cars this year. And then there are the local-to-Miami brands entering the fray, like Casa Tua, described by one real estate insider as “a beloved South Beach Italian restaurant whose whole charm was being an in-the-know secret garden Italian restaurant.” Now it has an 80-story tower “in soulless Brickell.” “As usual with Miami, we take a good idea and turn it into a parody of itself with no shame whatsoever,” he says.

Bazeli thinks this is just the beginning. “I think the next phase of this evolution will be a stack of brands on any given project, with a dominant brand that sets the tone, then other partnerships associated with wellness or culinary or the arts,” he says. He pointed to the Four Seasons Surf Club as an example of this: architecture by Richard Meier, interiors by Joseph Dirand, hospitality by Four Seasons, food by Thomas Keller. “Luxury buyers are attracted to the idea that every facet of their lifestyle is effectively branded.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/CFMGUNE5BZCU7J3QP5NZU2IYMI.jpg)