‘An eye-opener.’ Miami Heat, community leaders honor 162 Black incorporators of Miami

Clyde Corley had no clue about the 162.

The Florida International University graduate had been in South Florida since the 1980s yet a significant part of Miami’s history – namely that 162 Black men helped to incorporate the city – was not something he had learned. Until tonight.

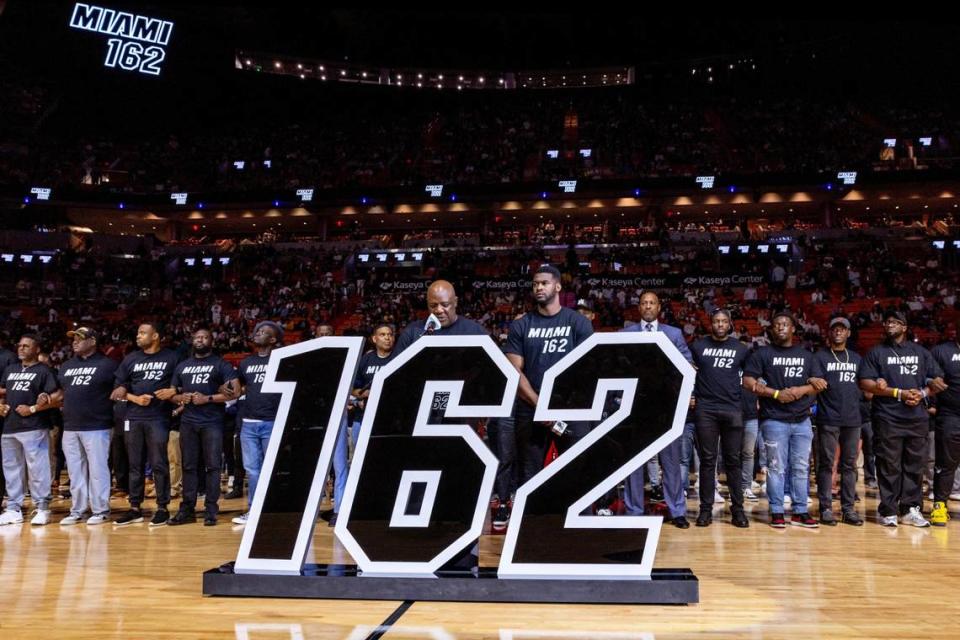

Corley was one of the more than 150 Black men who gathered on the court during halftime of the Miami Heat’s 116-104 victory over the San Antonio Spurs in order to share the history of Miami’s Black incorporators.

Poet Branden Wellington delivered a rousing spoken word piece while Jason Jackson gave brief speech as the men, all of whom locked arms and donned shirts that read “Miami 162,” spanned across the court.

“I thought I knew a lot about Black history,” Corley said. “It was an eye-opener for me. It needs to be taught.”

The idea to honor the 162 Black incorporators came courtesy of Heat Chief Marketing Officer Michael McCullough. Despite having lived in Miami for nearly 30 years, he first discovered the 162 during a tour of Overtown in 2020.

Gov. Ron DeSantis’ initial rejection of the AP African American Studies course as well as Florida Board of Education’s updated education standards, part of which said enslaved people benefited from their bondage, only emboldened McCullough to spread knowledge about the Black incorporators.

“History is being rewritten by folks,” McCullough said. “Tonight’s an opportunity for us to share a piece of history that nobody knows and give it chance to be told without letting anybody reshape it.”

Added McCullough: “We have a duty and an obligation to those fans who have supported us since 1988. Part of that responsibility is to use that platform that we’ve been given to speak up, support and reflect Miami.”

‘We made Miami’

Three-time All-Star Bam Adebayo was one of the Black men who participated in the halftime festivities. A vocal advocate for the rights of Black Americans, Adebayo too had no idea about the 162 until recently. He had no doubt that the history was “swept under the rug” but believed Wednesday night was an important step in spreading the word.

“It was a really cool moment,” Adebayo said of the experience. “Black people have been part of so much history that has been rewritten or not told. It’s good to have that piece of knowledge to know that, for Miami to become Miami, Black people had to be there.”

The true history of what happened on July 28, 1896 is something that can’t even be found on the city of Miami website. At the time, Florida required at least 300 registered voters for a city to incorporate. There wasn’t enough white men so under the strict instruction from their bosses, 162 Black laborers, most of whom were Bahamian and worked on Henry Flagler’s railroad, were told to go attend a vote. That would be the last time Black Miamians could vote without fear of intimidation until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“We made Miami,” Dorothy Fields, the founder of The Black Archives, said in 2021, the same year that the Miami Herald launched The 44 Percent, a Black-centric newsletter named after the 162 incorporators. “Those first 50 years, without the Black laborers, we would not have had Miami moving forward and certainly not what we have now. Not enough credit is given to the laborers.”

Added Adebayo: “Stripping away their voting rights stripped away their history.”

As the history of the 162 incorporators now weaves its way into the fabric of the larger Miami community, there’s renewed optimism that they will not be forgotten again.

“To be able to just shed light and share the information,” Adebayo said, “you can change a lot of people’s outlook.