Revisiting Vicki Hendricks’ ‘Miami Purity’ with Alex Segura ‹ CrimeReads

I didn’t know what to expect from a novel called Miami Purity. Was it about nuns, or one of those creepy abstinence-only pledges for teens? I had no idea that the novel was a neo-noir cult classic, one that Megan Abbott in her introduction lauds for “its audacious and subversive play with a tradition it clearly both savors and lays bare.” Nor was I prepared for the voice of Sherri Parlay—former stripper, recovering good-time girl, and one of the horniest women in the history of American fiction—who bursts on to the scene declaring, “Hank was drunk and he slugged me—it wasn’t the first time—and I picked up the radio and caught him across the forehead with it.”

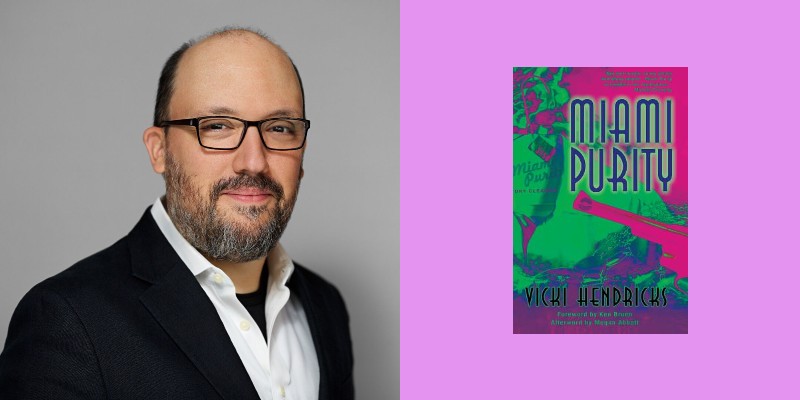

I should have had more faith in Alex Segura, the acclaimed writer of Secret Identity (which was nominated for the Lefty, Anthony, Macavity, and Barry Awards and won the LA Times Book Prize), as well as many other works. I wanted to talk to Alex not only because I love his work, but also because he’s an unabashed fan of the genre, with a seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of both the past and present of crime fiction. Not only was Miami Purity more interesting—and much dirtier—than I expected, but it’s written with an ease, a fearlessness, and a sharp wit that I know will bring me back to re-read it again and again.

Why did you choose Miami Purity by Vicki Hendricks?

So many reasons. For one thing, I think it’s a very tightly written book. It’s fairly short, and it’s unabashedly a very sexy book, and Hendricks is a really descriptive and evocative writer. It’s kind of the Venn diagram of things that interest me: Miami, noir, complicated protagonists. It was also one of the first crime novels where I saw my hometown described accurately.

How do you define the term noir, and what in this novel feels particularly noir-ish to you?

I’m so happy that you asked that question, because it’s something that I’m a real stickler about. I think that over time, noir has become kind of a catch-all marketing term, but I think of it as something very specific. It’s where a character is painted into a corner by their own design, like their own mistakes or choices have put them in an impossible situation. And it’s usually relating to some kind of primal urge. It’s not like a plan that goes awry; it’s that they’ve made a mistake based on lust or greed or vengeance. They’ve chosen poorly, and now must pay the consequences. And that’s the story.

And the thing about noir is that there’s never a tidy resolution. You don’t get the happy ending where they kind of ride off into the sunset; it’s usually pretty bad. Miami Purity is very much a noir, a neo-noir, in that bad things happen to people because they make bad choices. And I find those kinds of stories fascinating because it feels like real life, where few things are tidy, and few things are resolved easily.

I love that. Sometimes when I think about crime subgenres, I want to define them in terms of externals, or questions of narrative technique. But you’re talking about an existential definition.

Yeah, it’s not so much a plot thing. It’s not like a thriller, where you go in expecting certain elements, or a PI novel, where you obviously have to have a PI and very specific tropes, inverted or not. Noir is a feeling, it’s a vibe, it’s about the gray areas of life. What I love about Megan Abbott’s books is she takes the elements of noir and transports them into the most unlikely places: cheerleading, science, gymnastics, dance. And often she has these female protagonists at odds with each other, which flips the script on the tropes in a really good way. And I think you see the DNA of that in books like Miami Purity.

I’d never heard of this novel before you suggested it, and my first thought was What a weird title. I love what Hendricks does with the setting of the dry cleaners, though, and it does so much work in the novel in terms of plot, theme, etc. Can you talk about that setting?

It’s just such a great like workman-like setting. It feels very blue collar, but also a little decrepit. It seems like things are about to fall apart for everybody there. Like everyone is on the brink of something bad.

And yet they’re cleaning and purifying, and that irony works so beautifully.

Yeah, the idea that they’re purifying your clothes or purifying anything when you have these sordid schemers working there, it’s pretty wild.

Crime writers are always trying to come up with fresh and original ways to kill someone. Without giving any spoilers, I thought Hendricks did a particularly good job with this. Is this something you’ve ever struggled with in your own work?

Yeah, you want to make it memorable. There’s not a lot of bloodshed in Secret Identity, but for the Pete Fernandez novels, which are more action-oriented PI stories, I definitely try to make the death as interesting and memorable as possible, because that’s part of the fun. For me, usually, it’s more the surprise of the death that I think about—like, which character is the reader just assuming will live? In Silent City, my debut, I blew up one of Pete’s closest friends in the first half of the book, and people still ask me about it. You want to remind the reader that everyone is risking their life.

You mentioned you know that you love the novel partly because of the way it evokes Miami. Can you say more about that?

I think a lot of people presume that Miami is a lot like Miami Vice, or some kind of cool tropical paradise, when it’s really much more complicated and nuanced than that. Miami is a sprawling, diverse city that has lots of interesting nooks and crannies in terms of neighborhoods and cultures. The fact that it’s this very combustible place that’s painted over with a shiny tropical coating is really fascinating to me, and something I think about a lot in my work, and also in my life. You visualize it as this beautiful oasis of paradise, but there’s a dark undercurrent there that this novel taps into in a way that I haven’t seen in other Miami novels. It shows you the cracks in the veneer, and the dangerous stuff happening beneath it.

You mentioned the sex scenes earlier. There are a lot of them, and they’re pretty explicit. What do you think Hendricks’s intention was there?

I think she was challenging the perception of what was expected of female writers at the time. I think she went a long way toward showing that it’s okay for anyone to write these kinds of scenes, especially when it’s relevant to the book and adds to the tone and the vibe of the story. It just makes the book that much more noir and lurid and evocative. She also has a great command of description and her prose is just wonderful, so it becomes a really hypnotic experience.

That’s good context, and it’s interesting to think about how that aspect of the novel flips the script on some of those noir tropes. Sherry’s not at all a femme fatale—she’s someone with her own appetites and her own desires, and she’s acting those out rather than reacting to other people.

Exactly. Sometimes we think of the femme fatale as this emotionless viper out to get what she wants, and Sherry’s definitely not like that. She’s got feelings and conflicts and she also has a sex drive, and so she feels like a very developed, three-dimensional person. You just want to keep reading this story so you can keep hanging out with her. The minute you meet her, she feels alive.

I really loved the ending, which was such a tone shift from the rest of the book—it’s so quiet and almost elegiac. It’s kind of a left turn, but in a very effective way.

I had a similar reaction. As a reader, I appreciate it when writers take risks and don’t do the safe thing or the tidy thing. I read a book recently that I won’t name, but I was having a great time reading it, and then it ended how I expected it to end and that was fine. But then it made me a kind of bummed me out that there was no surprise, no leveling up—the credits just rolled and everything happened as expected. This book does the opposite, and kind of subverts your expectations for it—definitely levels up, because it has a subtle tonal shift, and also goes in a direction that, at least for me, I didn’t see coming. That’s really pleasant to me as a reader, because it keeps you on your toes. And it felt more in tune with what noir is—more primal and less meticulously plotted and precise.

To me, if everything had been tied up with a nice little bow, it would have been easier to leave the novel behind. But I know it’s one of those stories that will haunt me, because there’s some ambiguity there and some questions left unanswered.

It’s something I try to keep in mind in my own work, that not every thread has to be resolved, because that’s how it works in the real world. Readers are smart. They will pick up what you’re trying to do and will appreciate the risks you take as a writer. Not every reader wants the generic, store-brand of story. I always hope that risks and surprises are appreciated. But at the end of the day, we’re our first readers, and our goal should be to entertain ourselves. That’s my mission usually: what book do I want to read? How would I appreciate it rolling out? Odds are, if you enjoy your story, there’ll be plenty of others that do, too. So, yeah, not everything has to be tied up. Maybe there are some questions that are put to rest, but there are always a few stragglers too. In this novel, we’re watching these messed up, complicated people that are bumping into each other and doing bad things to each other, and that’s how life is sometimes. It’s gray, messy, and not at all organized.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about the impact it’s had on your work?

Yeah, talking about it now has clarified some things for me. At the end, you feel like you’re wanting more, but not in the way where the story feels incomplete. That’s a testament to character and a testament to realistic, sharp writing and great dialogue. And also she taps into the vices and the dark thoughts that we all have, and very rarely speak out or share or maybe even put on the page. Sometimes as writers we want to be cautious and safe, and this novel is a really good reminder not to do that. Dig deep and shine a light on those dark thoughts, because you’re not alone and people will be drawn to them.