The Luxury French Real Estate of Alleged Latin American Money Launderers and Officials Accused of Corruption

High-end French real estate has long attracted illicit funds. Analysis by OCCRP’s Latin America team and partners shows how alleged money launderers, officials accused of corruption, and other dubious figures have bought property in Paris and elsewhere.

Key Findings

- The in-laws of a Venezuelan minister targeted in a massive international corruption investigation owned a 2-million-euro Paris apartment.

- A Venezuelan linked to an alleged scheme to take funds from the state oil company bought over 20 million euros’ worth of property.

- The son of a former Brazilian minister investigated for corruption owned a 1.4-million-euro Paris apartment.

- The undeclared Paris apartment of a former Peruvian president investigated for corruption was quietly sold for 1.4 million euros in 2013.

The second-floor balcony of an ornate Parisian property overlooks the street near the Arc de Triomphe. Inside, a stylish hallway leads to a courtyard filled with plants. A doorbell reads “Zacarias” — but when a reporter rings, no one answers. Some neighbors say they don’t know the family; others say they haven’t seen them since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The apparently vacant apartment was bought in 2016 by a company set up by relatives of a former Venezuelan cabinet minister whose family is accused of handling tens of millions of dollars in suspected bribes. They are just one example of several high-profile Latin Americans investigated for corruption or criminal activity who have sunk money into French real estate, an investigation by OCCRP’s Latin America team and its partners found.

Other buyers of high-end French listings included a former Peruvian president suspected of taking bribes, a Venezuelan investigated over allegedly fraudulent dealings with the state oil company, and the son of a former Brazilian minister investigated for alleged corruption.

In all but one of these examples, the people were investigated in connection with Operation Car Wash (“Lavo Jato”), a massive corruption and money laundering scandal in Brazil that revealed billions of dollars in state funds had been siphoned away in corrupt deals.

🔗Data Analysis

OCCRP’s member center the Bureau for Investigative Reporting and Data (BIRD) downloaded, scraped, and processed information published by the French government in different datasets, including French companies’ beneficial owners, directors, and real estate holdings, as well as geocoded data about land plots.

To make the information easier to search, BIRD created a search engine that allowed reporters to connect the dots between properties and the people behind the companies that own them.

Reporters first identified people of public interest, such as heads of state and government, other politicians, and relatives of officials who had been investigated or involved in corruption cases.

Once their properties were identified, reporters sent requests to France’s property registry services — known by its French acronym, SPF — to obtain deeds of sale and other documents. These revealed the names of the notaries involved and additional details of the transactions.

Further analysis of the data was carried out by Transparency International, Transparency International France, and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective.

France’s abundance of high-end property, particularly in Paris and on the French Riviera, make it an attractive destination for dirty money. While the country has relatively open property registries, anti-corruption advocates say lax enforcement and loopholes still make it possible to use French real estate purchases to launder money and hide illicit funds.

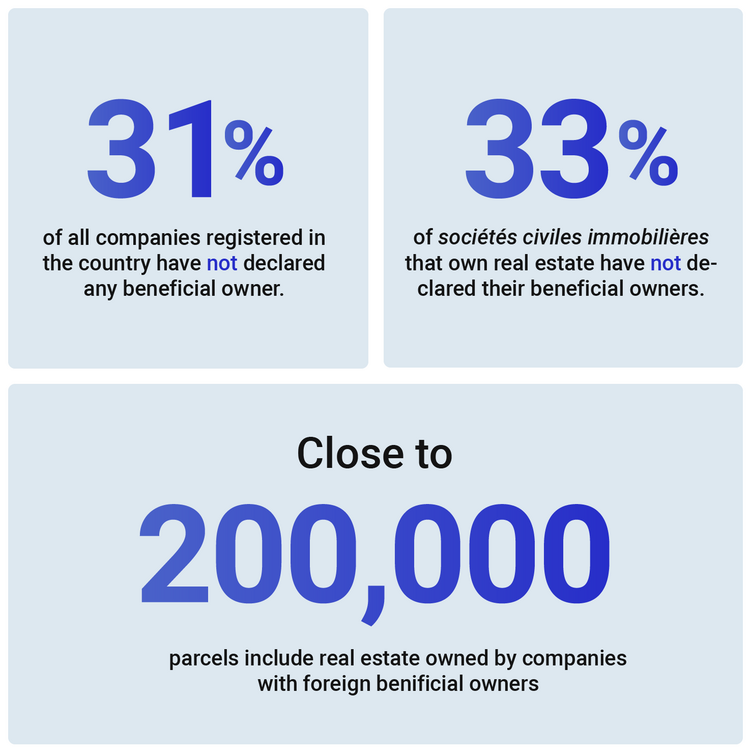

As a result, over two-thirds of French real estate owned through companies is held anonymously, Transparency International and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective said in a report based on available data on French company and real estate ownership.

“We have known for a long time that luxury French real estate is hot property for criminals and the corrupt looking to stash and clean their ill-gotten gains. Transparency measures of recent years should have been game-changing, but we have a long way to go to ensure that these tools achieve their full potential,” Maíra Martini, an expert on corrupt money flows at Transparency International, said in a statement accompanying the release of the report.

William Bourdon, a French lawyer and anti-corruption advocate, said that the “prestige” of places such as Paris, the Caribbean island of Saint-Barthélemy, and the French Riviera, can encourage international money laundering. “The result is a particularly attractive real estate market, which makes it possible to launder substantial sums,” he said.

Credit:

Edin Pasovic/OCCRP

Figures taken from a report by Transparency International France, Transparency International, and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective.

The findings highlight the importance of “beneficial ownership” registries, or records of who owns what. Such information forms a crucial part of the database, but has become harder to obtain in some countries after the European Union’s highest court shot down rules last year that had required member states to keep such information available.

Eight member states immediately closed their registers to the general public after the decision. France initially restricted access to its register, but then announced the registry would remain open “pending the adoption of a new legal framework at the EU level.”

Here are some of the key findings from the investigation:

Venezuela: In-Laws of Minister Accused of Taking Bribes Owned 2-Million-Euro Paris Apartment

Credit:

James O’Brien/OCCRP

Reporters found that close relatives of Haiman El Troudi, former transport minister of Venezuela, own a 2-million-euro apartment in Paris. El Troudi served as transport minister from 2013 to 2015, and then as a member of parliament from 2015 to 2020.

The apartment, located on the exclusive Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, is held in the name of a Paris-registered company — Saint Mathis 238, since renamed SCI Republic — which was set up in 2016. The owners of the company are El Troudi’s mother-in-law and her son.

A couple years before the apartment was purchased, tens of millions of dollars in suspected bribes from Odebrecht, the Brazilian construction firm at the heart of the “Car Wash” scandal, flowed into multiple bank accounts which were controlled by El Troudi’s wife, Maria Eugenia Baptista Zacarias, and his mother-in-law, Elita del Valle Zacarías Díaz, according to European investigators.

Credit:

Audrey Travère

Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris.

A 2020 Portuguese investigation document — first reported by the Miami Herald and Armando.info — shows that Portuguese investigators believed El Troudi’s wife was behind a Panama-registered offshore company, Cresswell Overseas S.A., which had received more than $90 million in alleged bribes from Odebrecht.

A separate set of documents from Switzerland, seen by reporters, showed that Swiss authorities had found that El Troudi’s wife and mother controlled eight bank accounts in the country, which collectively held 42 million euros. The authorities linked certain payments to contracts to build the Caracas metro system, which El Troudi was overseeing.

In July 2017, Venezuela’s state prosecutor’s office publicly stated it would summon the two women for alleged involvement in the bribery scheme. But in 2018, a Venezuelan judge dismissed the case against El Troudi’s wife and mother-in-law. The prosecutor assigned to the case said he was forced into exile the same year. El Troudi does not appear to have faced any charges.

Portuguese and Venezuelan authorities did not respond to requests for comment on the case’s status. The Swiss attorney general’s office declined to comment. Reporters attempted to reach El Troudi by text message, and left letters at addresses listed for his family in French documents, but received no reply.

The Paris property is not far from the historic Champs Elysées and Arc de Triomphe. When reporters visited, they found the name “Zacarias” on the doorbell of a seemingly empty apartment.

Reporters were also able to link El Troudi’s mother-in-law and her son to two other Paris apartments, one in the same building and another on the same street. French registry documents show that a company called Santa Elena Estates Inc. bought one of these apartments for about 2.3 million euros and the other for about 1.2 million euros, both in July 2012.

Santa Elena Estates Inc. was set up in the Caribbean island nation of St. Kitts and Nevis in March 2012, just a few months before the properties were purchased, and its directors were listed as Elita del Valle Zacarías Díaz, and her son Pedro Donaciano Baptista Zacarias, according to documents found in the Pandora Papers, a massive leak of documents obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with OCCRP and partners.

French records show that one of the properties — the one purchased for 1.2 million euros — was sold in November last year for around 966,000 euros. The records show Elita and her son were still directors of Santa Elena Estates at the time of the sale.

Venezuela: Businessman Reportedly Investigated for Money Laundering Bought 19.9 Million Euros Worth of French Land

Credit:

James O’Brien/OCCRP

Property records show that Luis Oberto, a Venezuelan businessman reportedly investigated for money laundering, has bought multiple expensive properties on the French island of Saint-Barthélemy.

One of the companies, Bucefalus, was set up in 2012. From late 2012 to early 2013, it bought a plot of land and two connected properties — a main house and a smaller unit — on Saint-Barthélemy for a total of 19.9 million euros.

Another company, Ganesha, which Oberto owns with his wife, was founded in 2008 to acquire a three-bedroom villa on Saint Barthélemy for 2.24 million euros. In 2013, it exchanged this property, plus nine million euros, for a three-bedroom beachside villa worth 11.4 million euros. The beachside property features a swimming pool, garden, and covered terrace.

According to a 2019 report in the Miami Herald, Luis Oberto and his brother have been investigated for money laundering in the U.S. The report quoted sources familiar with the investigation as saying the brothers were suspected of receiving billions of dollars into Swiss bank accounts, which had been misappropriated through fake loans to the Venezuelan state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., known as PDVSA. Over $4.8 billion was allegedly embezzled through the overall scheme.

U.S. officials did not respond to requests for comment on the case, and U.S. court records did not show any ongoing case.

Last year, Venezuela’s prosecutor said an arrest warrant had been issued for Oberto and his brother, but no other details were immediately available. Venezuelan authorities did not respond to requests for comment on the case.

French records seen by reporters show that Ganesha and Bucefalus’ properties in Saint Barthélemy were seized by French authorities in February and March 2022 as part of an ongoing money laundering investigation led by the Paris prosecutor’s office.

Documents related to the probe, seen by reporters, said that the Bucefalus properties were purchased with money transfers from bank accounts held by two offshore companies — Violet Advisors S.A. and Welka Holdings Limited, both of which Venezuelan prosecutors had linked to the alleged PDVSA scheme.

Credit:

Andia/Almay Stock Photo

Saint Barthélemy island, where the Oberto brothers registered their company and acquired property.

Lawyers for the Oberto brothers did not respond to requests for comment.

Brazil: Son of Former Minister Targeted in ‘Car Wash’ Owns 1.4-Million-Euro Paris Apartment

Credit:

James O’Brien/OCCRP

Reporters found that Márcio Lobão, son of a former Brazilian senator, owned a 110-square-meter, three-bedroom apartment in the heart of Paris.

In 2019, Brazilian authorities filed money laundering and corruption charges against Márcio Lobão and corruption charges against his father, Edison Lobão, who they alleged had received some 50 million reais ($12 million) from Odebrecht and the waste management company Estre Group in connection with the Car Wash scandal.

Márcio was briefly detained, but his father was not arrested. The two are now on trial in Brazil’s Federal District Court.

In January 2021, Márcio and his brother Edison Filho were also targets of a search and seizure operation, an offshoot of the investigation that had detained Márcio in 2019. Charges were not brought against Filho and the current status of that case is unclear.

The Paris property, located near a Gucci store in the wealthy sixth arrondissement, was purchased for 1.4 million euros in October 2008 through his company SCI Guignard, where his children and wife were also partners. The building is cast in the classic Parisian “Haussmann” style, and features an inner courtyard.

When reporters visited the property in April 2023, they found a doorbell marked “Guignard,” but no one answered when they rang. A neighbor confirmed that Márcio was sometimes seen staying in the apartment, most recently in February. The property was not mentioned in Car Wash case court documents seen by reporters, though a judicial decision authorizing Lobão’s 2019 arrest did show he made deposits into bank accounts he held in France.

Lobão’s lawyer said that his client had properly declared all his assets. He also stressed that Lobão had not been found guilty of any of the allegations in the Car Wash scandal and said that the 50 million reais figure stated by the prosecutor was “incorrect.”

“It is important to note that the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has not succeeded in proving any of its accusations up to this moment,” he said.

Peru: Former President’s Paris Apartment Quietly Sold For 1.4 Million Euros in 2013

Credit:

James O’Brien/OCCRP

After serving a term as Peru’s president in the 1980s, Alan García fled the country in 1992 to escape the authoritarian regime of Alberto Fujimori. He came first to Colombia, where he was granted asylum, and later started traveling to France. Media reports from the time suggest he lived between the two countries until 2001.

In November 1997, García and his wife bought a four-bedroom apartment in the upscale 16th arrondissement in Paris, along with a cellar space and a separate small bedroom on the seventh floor in the same building, for about 2.5 million francs, worth around $430,000 at the time. The property is located on a quiet side street near the Avenue Henri-Martin thoroughfare.

Around that time, García and his then-wife set up a company called SCI FIDES, divided its shares equally, and donated them to their four children — all but one of whom were minors at the time.

Peru’s congress began investigating García for alleged corruption and illicit enrichment while in office. But the statute of limitations expired in 2001, and he returned to Peru that year and ran for president again.

As García campaigned, a congressman named Fernando Olivera filed a complaint with Peru’s attorney general about García’s purchase of the Paris apartment, according to media reports from the time.

García did not win that year, but eventually retook the presidency five years later. The income or asset statements he filed at the time only listed three properties in Lima. In the final year of his second term, 2011, García then said in a sworn statement that he did not have any movable or immovable property in the country or abroad.

In October 2013, García’s Paris apartment was sold, along with other properties, for about 1.4 million euros. By that time, Peru’s congress and its Public Ministry — a government entity similar to a prosecutor’s office — were again investigating García for alleged illicit enrichment regarding his property purchases in Lima.

After leaving the presidency, García was also caught up in the Brazilian Car Wash money laundering and corruption investigation. In April 2019, a preliminary 10-day arrest warrant was issued against him as prosecutors prepared charges that he took bribes from the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht. He committed suicide just as he was about to be arrested.

Reporters attempted to contact García’s wife through the family’s lawyer but did not receive a response.

Reporting by Eduardo Goulart (OCCRP), Angus Peacock (OCCRP), Romina Colman (OCCRP), Sana Sbouai (OCCRP), Daniela Castro (OCCRP), Gianfranco Huamán (Ojo Público), Alexander Lavilla (Ojo Público), Nelly Luna Amancio (Ojo Público), Valentina Lares (Armando.info), Abdelhak El Idrissi (Le Monde), Atanas Tchobanov (BIRD), Aldo Benitez (ABC Color), and Audrey Travère

Fact-checking was provided by the OCCRP Fact-Checking Desk.