One of Miami’s historic Black neighborhoods is changing. Hialeah wants a piece of it

Enid Pinkney has seen a lot of changes since she began living in her Brownsville neighborhood in 1958.

The end of legal segregation. The growth of its Black community. The changing demographics.

So when the historian heard that the city of Hialeah was looking to annex a portion of her northwest Miami-Dade County neighborhood, she wanted to make her voice heard.

“Whatever deal they put up with, we get the short end of the stick,” Pinkney, 91, said. When asked whether the neighborhood’s changing demographics motivated the plan, she said that Brownsville’s population is now nearly half Hispanic — 45.5% to be exact. “When I first moved out here, it was a Black community. Now, I’m totally against the [annexation]. Because all they want is money.”

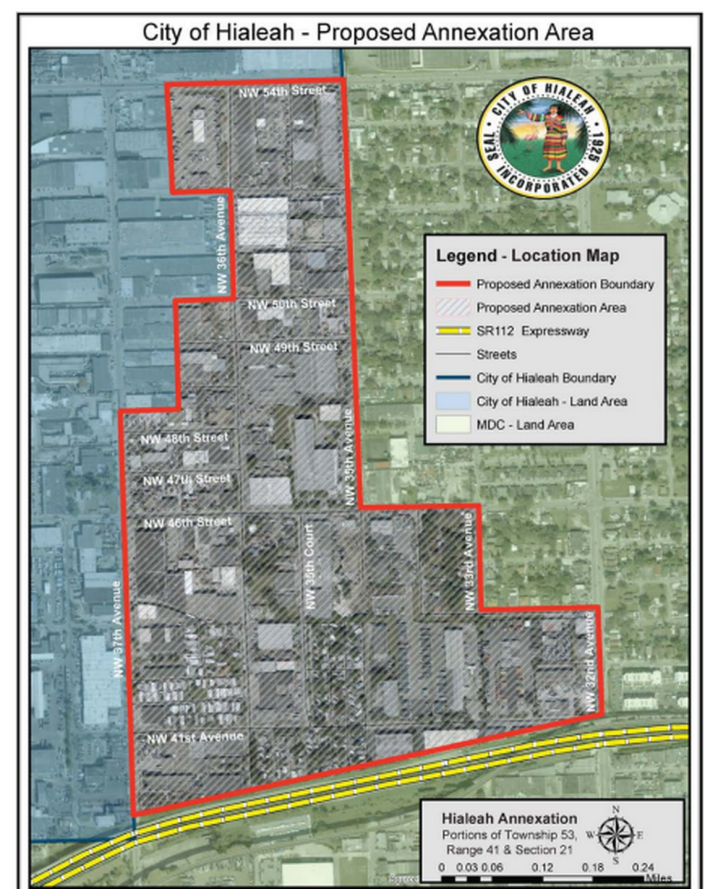

The proposed annexation includes 150.9 acres — about 0.24 square miles — of primarily industrial and commercial land as well as an area of 137 mobile homes by NW 54th Street and NW 37th Avenue. The majority of Brownsville, which is part of unincorporated Miami-Dade county, would remain with the county. It’s a small piece of land, but one that activists and residents seem prepared to fight for.

Brownsville was one of Miami-Dade’s first Black suburbs. Formerly a farming development that was recorded as Brown Subdivision on the city’s planning maps, Black Miamians began to settle in Brownsville — which spans from Northwest 62nd Street to 41st Street and Northwest 37th Avenue to 19th Avenue — in the 1940s. By the 1960s, the neighborhood became majority Black.

The community is home to a number of Black landmarks. There’s the Hampton House, a Green Book hotel that’s said to be where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a version of his “I Have a Dream” speech as well as the setting of “One Night in Miami,” a stage-to-film adaptation that explores a fictional meeting between Sam Cooke, new heavyweight champ Cassius Clay, Malcolm X and Jim Brown. There’s Lincoln Memorial Cemetery, where many of Black Miami’s heroes are buried like millionaire D.A. Dorsey and Florida Rep. Gwen Cherry. And there’s Georgette’s Tea Room, an attraction for many Black celebrities including Billie Holiday during the 1940s and ‘50s.

Like many things in the world of politics, Hialeah’s annexation plan boils down to finances. The proposal — prepared by engineering company The Corradino Group — demonstrated “the annexation area will provide fiscal strength to the city by increasing its tax base and allowing for significant creation of employment opportunities.” For residents of Brownsville, however, that’s the main issue: that the economic growth will benefit Hialeah, a city that’s roughly 96% Hispanic, according to recent Census data, rather than its primarily Black neighborhood. Although still in the exploratory phase, the proposal has already generated much opposition from the Brownsville community and beyond.

“If Brownsville wants incorporation or annexation, it has to be led by the people,” said Daniella Pierre, the president of the Miami-Dade chapter of the NAACP. “It’s not for Hialeah to decide.”

Nowadays, the community looks like any other working class suburb: ranch-style homes, public parks. But there’s also strip along Northwest 27th Avenue that used to be a bustling hub with mom and pop businesses. The prolonged construction of the Metrorail caused many stores to close as customers couldn’t access them in the 1980s, according to Kenneth Kilpatrick, the president of the Brownsville Civic Neighborhood Association. And Black Miamians have been leaving the area in search of more opportunity in North Miami-Dade and beyond, Pierre said.

“When those people leave, it’s not that they’re replaced by some families that would have that affinity for the community and the history that’s already in existence,” Pierre added.

Brownsville first

Between 2010 and 2020, the Hispanic population in Brownsville increased 91.4% (from 3,939 to 7,541), according to Census data. At the same time, the Black population decreased 23.8% (from 11,081 to 8,448). Many residents and activists believe these changes are why Hialeah is eyeing the area.

“It probably had something to do with their motivation with those numbers increasing,” Kilpatrick said.

Kilpatrick, however, didn’t want to make this an issue of race or ethnicity. Instead, he said this is an issue of preserving Black history.

“The African-American community can’t expect other races and colors to honor their history if they aren’t there to protect it themselves,” Kilpatrick added. “We want Brownsville to be remembered for all the rich contributions she has had to Miami-Dade County.”

Hialeah Council member Jesus Tundidor, who sponsored the plan to annex industrial area of Brownsville, maintains that “demographics has nothing to do with the plan” – though the residents of the trailer park inside the area of the proposed annexation are primarily Hispanic.

“Our plan is to annex the industrial area, there is nothing to do with residential area,” Tundidor said, referring to the vast majority of the neighborhood that would remain untouched. “In fact, that industrial area does not belong to Brownsville but to Miami-Dade County. We are not taking away the industrial area from Brownsville. It had nothing to do with Hispanic residents.”

In the days after the plan was announced, more than 100 Brownsville residents and activists attended a Hialeah city council meeting to voice their displeasure. Pinkney, Pierre and Kilpatrick all took turns explaining their opposition. Kilpatrick said the annexation would eliminate Brownsville’s “economic potential.”

“Miami-Dade County for many decades has recognized the proposed industrial area as an economic recovery zone,” Kilpatrick said on April 26. “Brownsville is opposed to any municipality taking advantage of any economic potential in the area before Brownsville does.”

Former District 108 representative Roy Hardemon shared a similar sentiment at the meeting, explaining that “taking the economic zone out of the neighborhood will make us eat each other.”

“Brownsville is a 2.28 mile neighborhood, even though you took the houses out of the plan, taking the industrial area from us is like putting two chickens in a cage and not feeding them,” Hardemon said at the time.

For Pinkney, however, Miami-Dade’s history of broken promises tells a cautionary tale. She, for example, was one of the residents of Overtown who was forced to move in the 1960s for the sake of “urban renewal.” Pinkney sees the annexation of the industrial part of Brownsville as the first step to a similar plan that would eventually erase the neighborhood’s history.

“I’ve seen too much,” Pinkney said. “I’ve lived too long.”