The Wild Story Behind How Michael Mann’s Movie Got Made

Television-to-film adaptations like that of Michael Mann‘s 2006 film Miami Vice have long been a common endeavor in the entertainment industry. With an endless list of iconic and beloved shows to choose from, filmmakers consistently show an eagerness to capitalize on nostalgia and audience-driven appreciation in translating the episodic format to the big screen. On the whole, many of these adaptations go on to great success, with franchises like Star Trek and Mission Impossible serving as examples that both honored and built on their respective source material. Some efforts, however, are not so fortunate and find themselves either largely forgotten or relegated to cultural obscurity. One such film is 2006’s aforementioned Miami Vice, an adaptation written and directed by the man who originally helped launch the fan-favorite television series 22 years prior.

Michael Mann, widely-known for critically-acclaimed films like The Last of the Mohicans, Heat, and The Insider, is known for immersing himself and audiences into the high-stakes environments in which his films are set. With particular attention to and an emphasis on realism, Mann also has a reputation as a demanding and audacious auteur whose vision requires the tireless efforts of those around him. Jamie Foxx, who would star as Ricardo Tubbs in Miami Vice, previously worked with the filmmaker in 2001’s Ali and 2004’s Collateral. It was during the making of the former that Jamie Foxx suggested the idea to Michael Mann of adapting Miami Vice into a feature film. Years later in mid-2005, as one of history’s most unruly Atlantic hurricane seasons was kicking off, production on Miami Vice commenced in various locations throughout South Florida, the Caribbean, and South America.

‘Miami Vice’ Had a Troubled Shoot

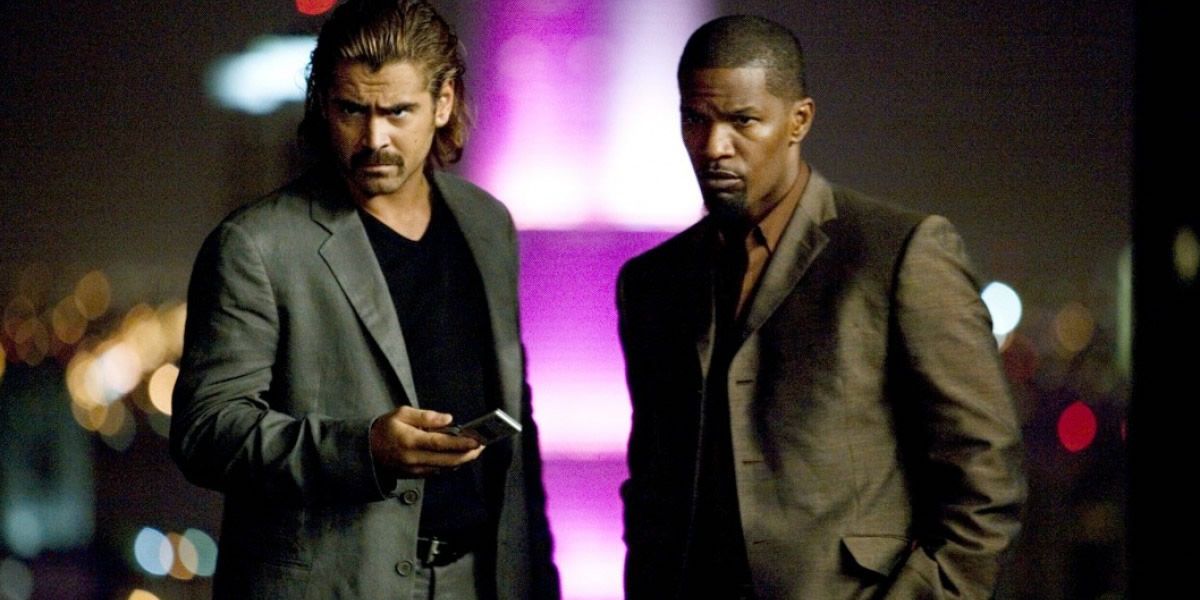

When cameras began rolling in the summer of 2005, Miami Vice was already a cinematic undertaking with high expectations. Michael Mann’s previous film, Collateral, saw great success with critics and audiences, which was likely helpful in the filmmaker securing a hefty budget well over $100 million for his new project. With a strong international cast that included Colin Farrell, Naomie Harris, and Gong Li, Mann’s film would center on the professional and personal lives of Miami detectives, Sonny Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs, as they go undercover to infiltrate a South American drug cartel. As with Mann’s earlier crime epic, Heat, the line between professional and personal blurs when Crockett enters into an affair with a kingpin’s business manager, raising the stakes for the already at-risk detective duo.

On the other side of the camera, the stakes were high for Mann, as well as his cast and crew, and it didn’t take long for the film’s shoot to hit some snags. While filming stateside in South Florida, the cast and crew were frequently plagued by inclement weather. According to a crew member, one such incident involved Foxx and Farrell driving a convertible with its top down on a Miami road. A tropical storm blew out the windows of a high-rise building and sent glass falling to the street, damaging the car and narrowly missing the actors. Mann stated about the close call, “You bet it was dangerous. As soon as we heard there were winds that high, we immediately wrapped.” In addition, Hurricane Wilma complicated the film’s production when it made landfall in Florida in October, forcing Mann to delay and rework the shooting of a critical scene.

Perhaps most infamous were the safety issues faced by Mann and company while shooting in the Dominican Republic. Mann’s creative habit of striving for authenticity took his cast and crew into some areas so dangerous that even members of law enforcement would choose to avoid. The production hired private security, which included local gangsters and members of the military. After a violent clash between a police officer and solider that resulted in a shooting, the cast and crew dispersed and Jamie Foxx fled the country with no intention of returning to complete the film’s originally scripted ending.

‘Miami Vice’ Suffered from Egos, Demons, and a Creative Force of Nature

Earlier that year, Jamie Foxx’s career received the ultimate boost when he received the Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Ray Charles in Taylor Hackford‘s 2004 biopic (he also nabbed a Supporting Actor nom for Collateral). This boost would manifest in some of Foxx’s behavior during Miami Vice‘s production. According to Slate, Foxx was granted a private jet by Universal Pictures after refusing to fly commercially and, upon learning that his initial salary was lower than his co-star’s, was able to procure a raise while Farrell took a cut. After the violent incident that rattled nerves of those on set in the Dominican Republic, Foxx’s sudden departure forced Mann to abandon his planned ending for the film, thereby necessitating the shooting of a different ending altogether. A crew member stated, “Jamie basically changed the whole movie in one stroke,” and that the original ending would have been “much more dramatic.”

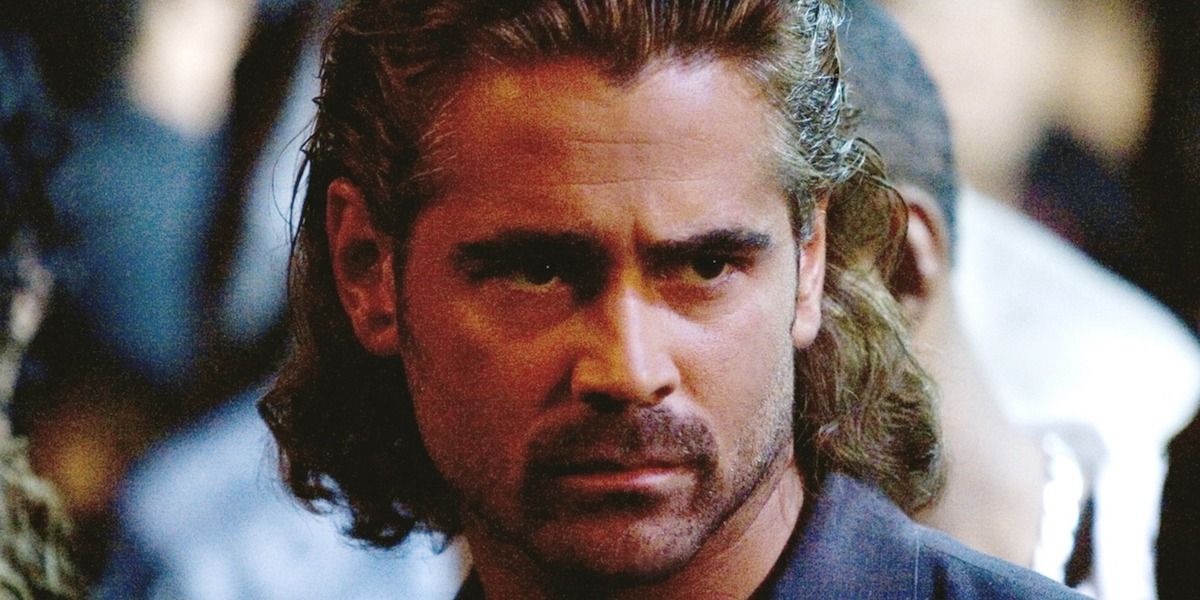

In addition, Colin Farrell brought his own baggage to the production, albeit in a more self-contained manner. Having cultivated a reputation among his show business colleagues as a performer who works hard and plays harder, the actor’s struggle with substance abuse and addiction reached a peak while playing Sonny Crockett. Colin Farrell reflected on his physical and mental state while making Miami Vice, stating, “It was literally the first time I couldn’t say to anyone around me, ‘Have I been late for work, have I missed any days, have I been hitting my marks?’ Because the answers would have been yes, yes, and no… I lost the ability to be confident that I could make a change myself.” Shortly after production wrapped on Miami Vice, the actor sought help for addiction.

Regardless of the turmoil surrounding the stars of his film, Michael Mann brought his own set of complications to the production. Known for being a demanding filmmaker, he inspired a variety of reactions among members of his crew, with some admiring the lengths he’d go to realize his uncompromising vision, and others recognizing the tension that can arise when working with a man so dedicated to his artistic convictions. One crew member quipped, “Michael dressed down everybody and humiliated everybody. He’s an equal-opportunity guy.” Another crew member seemingly appreciated the challenges of working with Mann when she said, “It’s about stretching when you work with him. His expectations might be high because he’s so creative. It’s just a standard he sets.”

$135 million, the film’s final budget, is a lot of money to be experimenting with, and Mann had a habit of changing his mind and reworking certain elements of the film on short notice. One can’t help but understand and sympathize with the feelings of uncertainty that such an improvisational approach to filmmaking could provoke, but Mann’s proven track record as a skilled and talented filmmaker meant that his financial backers would stick with him. Marc Shmuger, then Vice Chairman of Universal Pictures, said of the director, “I actually marvel at his ability to keep all of his creative options open. He’s fearless. He is willing to try everything. That’s a process that does involve wear and tear on everybody.”

‘Miami Vice’ Wasn’t Mediocre, but Misunderstood

When Miami Vice hit theaters on July 28, 2006, the reception among critics and the public was largely indifferent and unenthusiastic. It’s worldwide box office take capped at $164 million, which was certainly considered a financial disappointment given the film’s high production and marketing budgets. Some critics found it to be an example of style over substance, a film that placed emphasis on mood and tone, lacking a coherent and focused narrative. Others opined that while Farrell and Foxx were efficient as the iconic Crockett and Tubbs, they lacked the chemistry between Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas in the original series. The film’s darker, hard-edged take on the buddy cop genre also received mixed reviews.

Even some of those involved with Miami Vice, chiefly Michael Mann and Colin Farrell, have expressed reservations in the years since the film’s release. In a 2016 interview for New York Magazine, Michael Mann reflected on Miami Vice saying, “I don’t know how I feel about it. I know the ambition behind it, but it didn’t fulfill that ambition for me because we couldn’t shoot the real ending.” Colin Farrell said of the film in Total Film Magazine, “Miami Vice? I didn’t like it so much. It was never going to be Lethal Weapon, but I think we missed an opportunity to have a friendship that also had some elements of fun.”

In the years since Miami Vice‘s release, however, a loyal and dedicated contingent of viewers have led the charge in reappraising the film as a visionary and original approach to the crime genre. While it’s arguably muddled and unusual narrative was initially the subject of criticism and disappointment, some viewers believe this aspect of the film actually highlighted its visual and tonal qualities. Without an overt focus on the cause-and-effect nature of plotting and crystal clear characterization, the film prioritizes style and aesthetic over the nuts and bolts of traditional storytelling. In contrast to his tightly-plotted and classically structured Heat, Miami Vice bucks many of the conventions associated with crime films in pursuit of a cinematic experience reliant on a particular vibe and atmosphere. In making the film, Mann clearly had little to no interest in appeasing audience expectations of what an adaptation of the television series would look and sound like. His vision of Miami, unlike that of the series, avoids bright colors and cultural excesses, and instead presents a more dreary and stormy reality full of complicated characters who are all-too-human in their flaws and shortcomings.

In Scott Bowles’ USA Today review of Miami Vice, albeit not a positive one, he wrote, “All this movie has in common with its ancestor are speedboats, shotguns and drug-dealing Colombians.” Critic Steven Hyden, in writing about Miami Vice for its 10th anniversary, observed, “Given how ubiquitous remakes, reboots, and reimagined franchises have become, Miami Vice now seems like a refreshing curveball, a reminder that a visionary director empowered by a major studio can make an idiosyncratic work of art in the form of a would-be summer blockbuster. Even those who find Miami Vice indulgent or boring can’t accuse it of pandering to fanboys or exploiting tired nostalgia. It is, unapologetically, one of the most expensive art films ever made.” Both critics, although in disagreement over the quality of the film, are correct.

For better or worse, Michael Mann didn’t have hardcore fans of the series in mind when he made Miami Vice. Having already written and directed one of American cinema’s most revered crime films with Heat, one can assume the filmmaker, although revisiting material from his past, was consciously avoiding treading through familiar territory. While it appears unlikely that audiences will see Crockett and Tubbs on the big screen again, this iteration gave them a singular and tonally unique vision, effectively shirking the series’ ’80s aesthetic in favor of a modern crime epic that took itself seriously. While some argue that the film could’ve benefited from a lighter approach with a sense of fun, the end result proved to be a uniquely melancholy and atmospheric take on the genre. Its greatest strength is succeeding in standing apart from cinematic formula by boldly exploring the conflicts and consequences that arise when one’s professional and personal lives intersect.